![]()

COURTESY BY: https://www.hindustantimes.com/

Some time after President Xi Jinping landed in Ahmedabad on 17 September 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi broached the intrusion by Chinese troops in Ladakh’s Chumar. He asked President Xi to call off the People’s Liberation Army soldiers or he would have to assume that the intrusion was with his knowledge. PM Modi broached the subject again the next day, this time in Delhi. There had been no change in the ground situation in Chumar, a remote corner of the dry desert plateau of the western Himalayas. President Xi said he was “sad” that tensions between the armies had “cast a shadow” on his visit. The PLA backed down after President Xi wrapped up his India visit and reached Beijing.

The Doklam stand-off happened three years later, when Indian soldiers stopped the Chinese from building a road into the Doklam bowl. This would have allowed the Chinese military to move vehicles in South Doklam towards the Jampheri ridge that overlooks the Siliguri corridor.

Quite like the Chumar, the Doklam stand-off had been initiated by local commanders and was escalated to top military commanders. It ended eventually 73 days later after PM Modi flagged it to President Xi. Both leaders agreed that the standoff was not in the interests of the two nations, setting up the ground for thawing of the freeze in the relationship that led to the withdrawal from both sides.

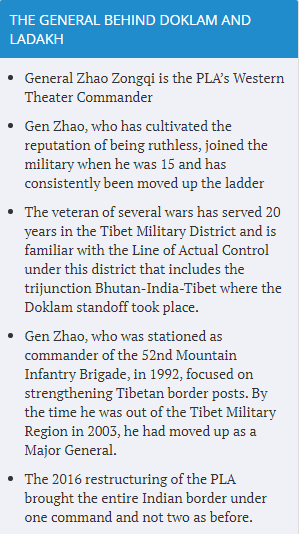

And this, by all accounts is how the Ladakh stand-off is so different from the ones in the past. There is one common denominator in Doklam and Ladakh stand-offs though. General Zhao Zongqi, the PLA’s Western Theater Command’s big boss.

“Our understanding is that the Ladakh standoff was driven from the top, unlike the previous two stand-offs,” a senior government official familiar with the developments told Hindustan Times. For one, because the stand-off was preceded by violent scuffles in two military districts before the bloody face-off on June 15.

The first was a violent clash on May 5-6 between Indian and Chinese patrols on the northern bank of Ladakh’s Pangong Tso. Scores of soldiers – from the Indian side and PLA’s Xinjiang military district – were injured in the skirmish involving 250 men.

A few days later, a second clash took place on May 9 when heated confrontation between Indian and PLA soldiers from the Tibet military district in north Sikkim’s Naku La area again led to violence. Four Indian and seven Chinese soldiers were injured during the face-off involving 150 soldiers.

The third, on June 15, was the bloodiest and led to the first casualties along the LAC in 45 years.

It is only at the level of the top commander that PLA soldiers under different military districts – the Tibet and Xinjiang military districts – would have responded with such striking similarity, an official said, referring to the skirmishes between soldiers in Sikkim and Ladakh in May.

Both military districts report to Gen Zhao, who is believed to be directing much of the action along with the Line of Actual Control. Officials, however, indicate that it was unlikely that Gen Zhao, who is not part of the Central Military Commission but has President Xi’s ears, would be acting on his own.

This would explain, a diplomat said, why the Chinese army appeared to be taking steps to prolong the stand-off even after foreign ministers of the two countries agreed to implement the understanding reached between top army officers on June 6 on de-escalation of troops from both sides. Or why the June 15 violent scrap still took place.